James Webb Space Telescope finds the faintest galaxy ever detected at the dawn of the universe

The James Webb Space Telescope has discovered the faintest galaxy ever seen, burning away the pitch-black gloom of the early universe 13 billion years ago.

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has identified one of the most distant galaxies ever seen — an ancient, nearly invisible star cluster so remote that its light is the faintest scientists have ever detected.

Called JD1, the galaxy — whose light traveled for roughly 13.3 billion years to reach us — was born just a few million years after the Big Bang. Back then, the cosmos was shrouded in a pitch-black fog that not even light could pass through; galaxies like this one were vital in burning the gloom away.

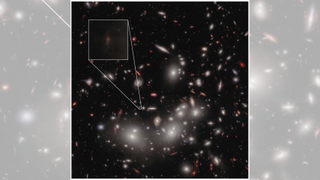

Twinkling from within the Sculptor constellation in the southern sky, JD1's light left its source when the universe was just 4% of its current age. The light crossed dissipating gas clouds and boundless space before passing through the galaxy cluster Abell 2744, whose space-time-warping gravitational pull acted as a giant magnifying lens to steer the ancient galaxy into focus for the JWST. The researchers who discovered the dim, distant galaxy published their findings May 17 in the journal Nature.

Related: Can the James Webb Space Telescope really see the past?

"Before the Webb telescope switched on, just a year ago, we could not even dream of confirming such a faint galaxy," Tommaso Treu, a physics and astronomy professor at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), said in a statement. "The combination of JWST and the magnifying power of gravitational lensing is a revolution. We are rewriting the book on how galaxies formed and evolved in the immediate aftermath of the Big Bang."

In the first hundreds of millions of years after the Big Bang, the expanding universe cooled enough to allow protons to bind with electrons, creating a vast shroud of light-blocking hydrogen gas that blanketed the cosmos in darkness. From the eddies of this cosmic sea-foam, the first stars and galaxies clotted, beaming out ultraviolet light that reionized the hydrogen fog, breaking it down into protons and electrons to render the universe transparent again.

Astronomers have observed evidence for reionization in many places: the dimming of brightly flaring quasars (ultrabright objects powered by supermassive black holes); the scattering of light from electrons in the cosmic microwave background; and the infrequent, dim light given off by hydrogen clouds. Yet because the first galaxies used so much of their light to dissipate the stifling hydrogen mist, what they actually looked like has long remained a mystery to astronomers.

"Most of the galaxies found with JWST so far are bright galaxies that are rare and not thought to be particularly representative of the young galaxies that populated the early universe," first author Guido Roberts-Borsani, an astronomer at UCLA, said in the statement. "As such, while important, they are not thought to be the main agents that burned through all of that hydrogen fog.

"Ultra-faint galaxies such as JD1, on the other hand, are far more numerous, which is why we believe they are more representative of the galaxies that conducted the reionization process, allowing ultraviolet light to travel unimpeded through space and time," Roberts-Borsani added.

To discover JD1's first stirrings from beneath its hydrogen cocoon, the researchers used the JWST to study the galaxy's gravitationally lensed image in the infrared and near-infrared spectra of light. This enabled them to detect JD1's age, distance from Earth and elemental composition, as well as estimate how many stars it had formed. The team also made out a trace of the galaxy's structure: a compact glob built from three main spurs of star-birthing gas and dust.

The astronomers' next task is to use their technique to unveil even more of these first galaxies, revealing how they worked in unison to bathe the universe in light.

Live Science newsletter

Stay up to date on the latest science news by signing up for our Essentials newsletter.

Ben Turner is a U.K. based staff writer at Live Science. He covers physics and astronomy, among other topics like tech and climate change. He graduated from University College London with a degree in particle physics before training as a journalist. When he's not writing, Ben enjoys reading literature, playing the guitar and embarrassing himself with chess.

-

RewKahn Reply

Would it be possible to get an "actual" distance to the galaxy rather than the age-distance of 13.3 billion light years? We know the universe is approximately 13.7 billion light years old, but also approximately 93 billion light years in diameter. What I'm asking, is how far away, not how far back in time, is the galaxy? Also, I'd really appreciate knowing how that distance is calculated since it's obviously not a linear relationship. Thanks.admin said:The James Webb Space Telescope has discovered the faintest galaxy ever seen, burning away the pitch-black gloom of the early universe 13 billion years ago.

James Webb Space Telescope finds the faintest galaxy ever detected at the dawn of the universe : Read more -

Harmonograms Instead of light-years, which is simply a yard stick equal to the distance light travels in one year, convert it to parsecs. The light we see is from an object about 4 billion parsecs distance. Note that the age of the universe is a time measurement and it's about 13.7 billion or so "years" old (not light-years). The actual physical location of the object whose light we are observing won't be known to us for 13.3 billion years, which is when that light will reach us; we only can observe it as it was 13.3 billion years ago - that is our current reference frame and reality.Reply -

RewKahn Reply

I understand we're seeing it as it looked 13.3 billion years ago, and that's it is no longer in existence. What I was trying to get at was where, within the 93 billion light years framework of the universe, we would place the position13.3 billion object. I'm trying to understand the implications of inflation in the ever-expanding universe, with its accelerating expansion rate. When one converts to distance using parsecs, it seems you're using a one-to-one conversion, i.e., linear, when we know the expansion of the universe not only isn't linear but its changing. How does one address that? (I've had math through tensor calculus; and while I read Guth's "inflationary Universe," I haven't kept up with developments in the field.)Harmonograms said:Instead of light-years, which is simply a yard stick equal to the distance light travels in one year, convert it to parsecs. The light we see is from an object about 4 billion parsecs distance. Note that the age of the universe is a time measurement and it's about 13.7 billion or so "years" old (not light-years). The actual physical location of the object whose light we are observing won't be known to us for 13.3 billion years, which is when that light will reach us; we only can observe it as it was 13.3 billion years ago - that is our current reference frame and reality.

I had the following conversation with some folks at STSI, which is probably pertinent:

Hi Rebecca,

Yes, you've got the main idea - the universe is expanding, and carries light with it, so that the things we are now observing with Webb are by now much farther away from us than the time it took for their light to arrive would suggest. Scientists often use "lookback time" when talking about these distant objects to mean how long did light have to travel to get here, and when we say an early galaxy is "13.1 billion light years away", it's the look-back time we're referring to. You are correct that because of the expansion of the universe, an object with a lookback time of 13.1 billion years is really more like 30 billion light years away. The furthest photons are from the Cosmic Microwave Background, ~45 billion light years away (depending on your exact cosmology used), and Webb isn't sensitive to these. What Webb sees are the first galaxies from a few hundred million years later.

Sincerely, the Office of Public Outreach.

I guess, in effect, they answered part of my question, because the object I was discussing with STSI was 13.1 light years, or 30 light years distant, not very much different in astronomical terms. (We used to joke pi was 1 or 10 depending on the order of magnitude you needed.)

I have queried far and wide trying to find how to calculate distances to astronomical objects, accounting for the expansion of the universe. No luck. If my question is too complicated to address in this forum, I'll understand. Could you then possibly provide a reference? Thanks so much.

Most Popular

By Ben Turner