HIV vaccine stimulates 'rare immune cells' in early human trials

The vaccine stimulated a set of one-in-a-million immune cells.

A new vaccine for HIV is raising excitement after its first in-human trials showed 97% success at stimulating a rare set of immune cells that play a key role in fighting the virus.

The vaccine approach is a new attempt to head off the fast-mutating human immunodeficiency virus, which has eluded vaccines in the past because it attacks part of the immune system directly and is good at evading other immune defenses. Developed by scientists at Scripps Research in San Diego and the nonprofit International AIDS Vaccine Initiative (IAVI), the vaccine is in Phase I clinical trials and has been tested in only 48 people so far.

However, the results of the trial generated excitement, especially because Scripps and IAVI will now partner with Moderna to make an mRNA version of the vaccine — a step that could lead to faster vaccine availability, according to Scripps Research.

Related: The 12 deadliest viruses on Earth

"With our many collaborators on the study team, we showed that vaccines can be designed to stimulate rare immune cells with specific properties, and this targeted stimulation can be very efficient in humans," William Schief, an immunologist at Scripps whose laboratory led the vaccine development, said in a statement. "We believe this approach will be key in making an HIV vaccine and possibly important for making vaccines against other pathogens."

A challenging vaccine

HIV vaccine research started in the 1980s, not long after the discovery of the virus that causes AIDS. However, progress has been slow, with only one two-vaccine combination — tested in the Thai RV144 trial — shown to have an effect. The results of that trial, released in 2009, showed a 31% reduction in infection due to the vaccine combination. That is too low to submit for regulatory approval, but the vaccine developers continue to study what does and does not work about the combination. Follow-up research suggested that this limited protection faded after about a year.

The virus is a difficult target for vaccination because it's expert at evading the body's antibody response. Antibodies are proteins that are primed to recognize a foreign invader, or antigen, and bind to that invader right away, neutralizing it or tagging it for destruction by other immune cells. Vaccines work by presenting a dead or harmless antigen to the immune system, allowing antibodies to develop without the threat of disease. But because HIV mutates quickly to avoid antibodies, a highly effective vaccine has yet to be developed.

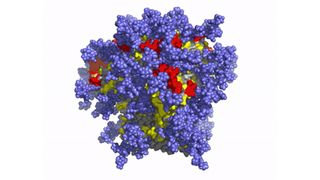

The new approach focuses on a rare set of antibodies known as broadly neutralizing antibodies. These antibodies can bind to the spike proteins on HIV, a part of the virus that doesn't vary much among different strains. The spike protein is the key the virus uses to enter cells, so it can't mutate much without locking the virus out.

The problem is that broadly neutralizing antibodies are secreted by only a handful — about 1 in every 1 million — of the immune system's B cells, Schief said. B cells are the cells that produce antibodies.

"To get the right antibody response, we first need to prime the right B cells," he said.

New technologies for new vaccines

The new approach targets this specific set of B cells with a vaccine compound called eOD-GT8 60mer. In the early safety trial, 48 healthy adult volunteers were given either the vaccine candidate or a placebo shot. The trials didn't directly test whether the vaccine prevented HIV infection but instead looked at whether the vaccine was safe and whether the participants who received the shot produced more broadly neutralizing antibodies than the comparison group who received a placebo.

The results, presented Feb. 3 at the International AIDS Society HIV Research for Prevention virtual conference, showed that the desired antibodies were found in 97% of the participants who received the vaccine.

There is a long road ahead for a potential new HIV vaccine, including follow-up trials to test the effectiveness and safety in large groups of people. The researchers hope that partnering with Moderna to use mRNA technology will help them piggyback on the safety and efficacy success seen in the company's COVID-19 vaccines, thereby speeding the process.

Originally published on Live Science.

Live Science newsletter

Stay up to date on the latest science news by signing up for our Essentials newsletter.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Most Popular

By Harry Baker